Search

Collected Writings and Historic Images of Washington, DC's Famed Dupont Circle Neighborhood

Featured Article

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

John Little: Irish Immigrant, Butcher, and Slave Owner

|

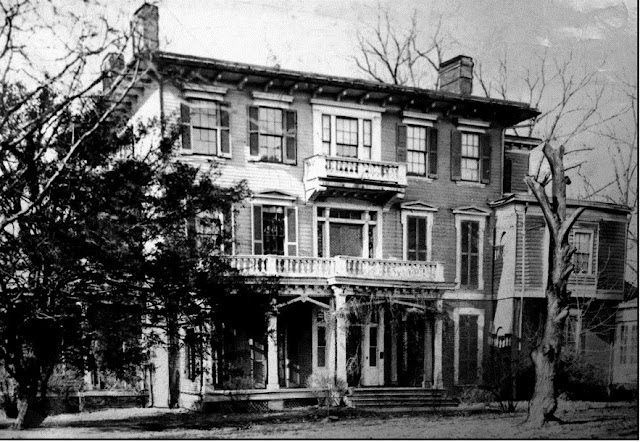

| Christian Hine. Author's collection. |

Little moved with his family into the house and then built a slaughterhouse into a hillside between what is now Champlain and Eighteenth Streets, about a block or two north of Florida Avenue where Slash Run once flowed and into which he would dump animal entrails and blood that then flowed downhill to the Dupont Circle area.

Little became very successful as a butcher and had a butcher stand at the original Center Market, then also known as “Marsh Market,” located at Seventh Street and Pennsylvania Avenue NW, now the site of the National Archives. With Little’s success, the size of his household, slave holdings and personal property grew quickly. Now needing more room, Little built a large three-story house on the west side of Columbia Road in the 1850s, now the location of Kalorama Park.

By 1860, a total of twenty-seven individuals were listed as living in the Little household, seventeen of whom were enslaved African Americans. By now, Little had multiple buildings in the area of today’s Kalorama Park that included the original manor house, a second house located where the Woodley apartment building stands today at 1851 Columbia Road that was razed in 1903, a carriage house, and outbuildings that probably served as slave quarters.

|

| John Little built his house in the center of what is today Kalorama Park. Author's collection. |

With the arrival of thousands of Union troops in Washington in 1861, one of Little’s female slaves, twenty-year-old Hortense Prout,, decided it provided an opportunity to make a run for her freedom. Little searched for her and found her in one of the Ohio Company camps that was tented out in Washington, “completely rigged out in male attire.” Hortense was then turned over to Little and taken to jail. Whether or not the Ohio Company was aware that Hortense was an escaped slave, or even that she was a female, is uncertain. It is also unknown what happened to Hortense after the war, but her mother stayed on the farm and continued to work for the Littles.

The Littles also took over the Hines’s family burial ground that was located at the corner of Columbia Road and Eighteenth Street to use, as John Little’s daughter Margaret recalled in 1915, as a burial place for family servants that never had stones to mark any of the graves. It is quite probable that the “servants” Margaret was referring to were some of the Littles’ slaves.

|

| John Little's farm. Detail from Albert Boschke's Topographical Map of the District of Columbia. 1858. |

John Little managed to continue to operate his cattle farm after his slaves were freed in 1862. By 1870, he was sixty-five years old, still farming and living with his wife and three grown daughters in the manor house in Kalorama Park. But by now, Little only had three black employees on the estate and was also taking in boarders. Little died in 1876 at the age of seventy-one and was buried at Congressional Cemetery. His estate was left to his five daughters who were not interested in continuing their father’s farming and butcher business themselves, and they began to sell off the land for development while continuing to occupy the family house.

The Little house had become a boardinghouse by the 1920s. In 1942, when the National Capital Park and Planning Commission acquired the property for use as a park, the house had already disappeared. As a result of Hortense’s attempted escape to freedom, the site of John Little’s house in Kalorama Park is now included in the National Park Service’s National Underground Railroad: Network to Freedom.

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

Popular Posts

William M. Galt House at 1328 Connecticut Avenue

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

William Hitt and Katherine Elkins: A Portrait of a Marriage...or Two

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

Levi and Mary Leiter: Washington, DC's Quintessential Parvenus and Buccaneers

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

The British Are Coming: The British Legation Moves to Connecticut Avenue

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

Comments

Post a Comment